Interview with Jason Page

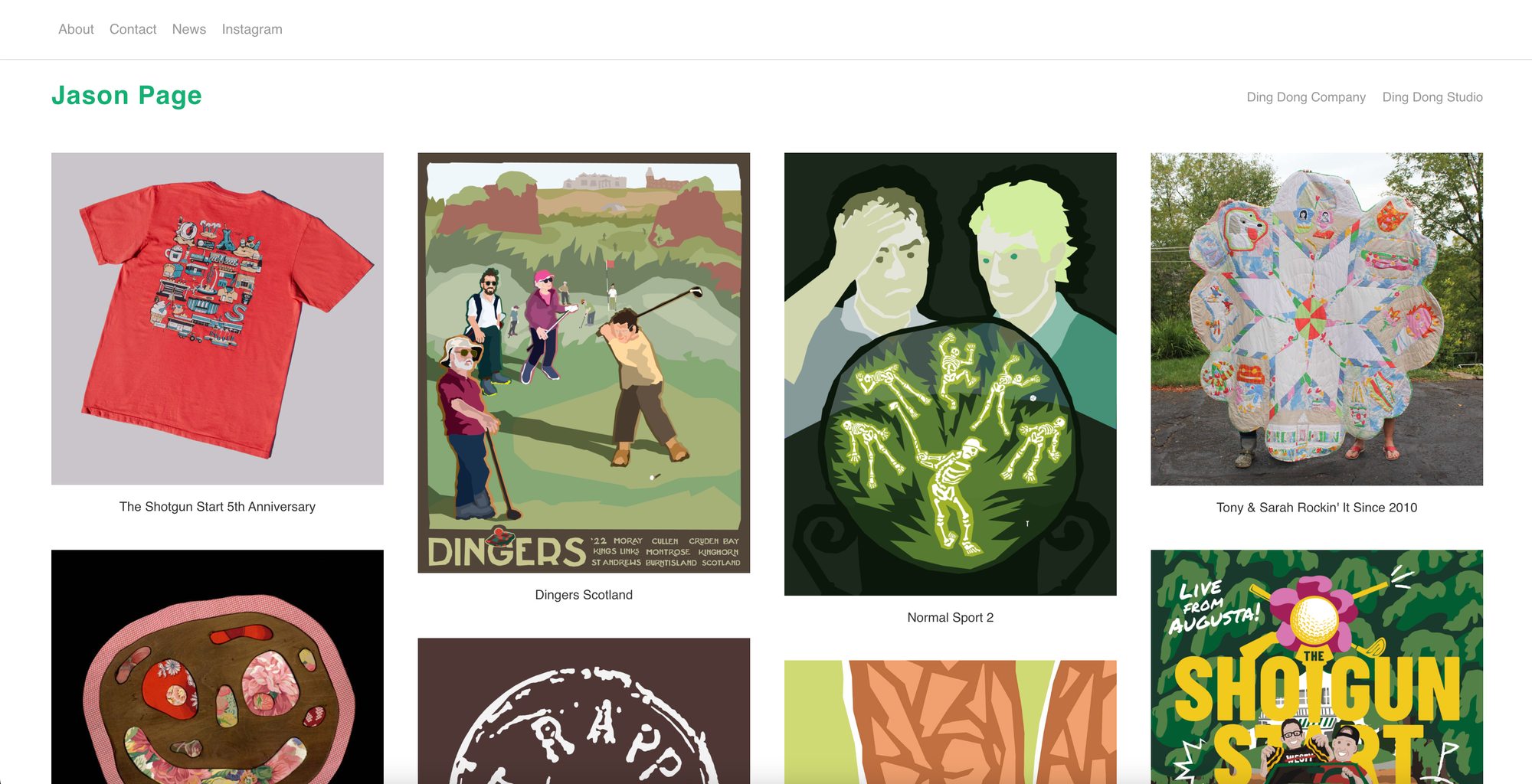

Meet Jason Page, a Professional Ding Dong (read: visual artist) who works with various forms of illustration and textile patchwork. He likes to play with the visual culture of his past — golf, quilts, and the American identity — with a Ding Dong style.

This Hotpot issue is an interview with Professional Ding Dong (read: visual artist) Jason Page.

Born in Coopersburg, Pennsylvania in 1990, Jason has been living in The Netherlands since 2010. He works with various forms of illustration and textile patchwork. He likes to play with the visual culture of his past — golf, quilts, and the American identity — with a Ding Dong style.

His commissioned work (Ding Dong Company) and autonomous work (Ding Dong Studio) combine various mediums and archived imagery/info to create new narratives. Most of his works are created as gifts, and many are made in collaboration with good folks.

This description was taken almost 1to1 from Jason's website.

Hopefully, you will enjoy reading this interview and his Ding Dong newsletter, where he talks more about the world around his work.

The interview has been run asynchronously via iMessage over the last two weeks. A lot of fun. I hope you will enjoy my conversation with Jason Page.

Jason Page [24.02.24 00:12 am]

Talking about what I do, there’s a mug on my desk that I keep my pencils in. It says, “My job is top secret, I don’t even know what I’m doing.” That sums up my creative practice. I call myself a Professional Ding Dong (read: visual artist). The professional side of that involves commissions and collaborations, making illustrations for the golf world, and quilts for people’s homes. The Ding Dong side is the creative freedom/flexibility that I seek in my work (and life, for better or for worse). I enjoy playing with illustration and textile patchwork to combine various mediums and self-archived imagery/info into new narratives. In a nutshell: my name is Jason Page, and I’m a Pennsylvania Dutch visual artist living in The Netherlands since 2010.

Andrea Brena [25.02.24 10:55 am]

With the last issue of Hotpot revolving around the idea of information, knowledge, and wisdom, I immediately thought of you and the role that archives play in your practice. I recall one of your graduation projects, the Nipple Booth, and I am curious to know how this element of your work has evolved over the last ten years.

Jason Page [25.02.24 07.23 pm]

The first Nipple Booth was the brainchild of Design Academy Eindhoven’s (DAE) student-run magazine Snor for its Super Nice issue (2011), which I was the editor of. International art school English is a funny, simplified language. DAE students used "super nice" for everything, but some of us at Snor were cynical about what we all really meant when we talked about design aesthetics. We wanted to find objective examples of super nice aesthetics, and we picked nipples to focus on. Obviously. The first nipple booth (imagine a green textile phone booth) was installed in the canteen for students to take anonymous nipple self-portraits. Since then, I’ve carried the Nipple Booth torch to the Eye Filmmuseum Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and lastly, at Art Museum Z33 in Hasselt, Belgium. To date, there are about 1200 nipples in the archive.

I haven’t presented the Nipple Booth since 2019, but it’s a good example of how I got started with generating archives of unique material. It’s always been about observing & combining. For my golf illustrations and textiles, I like to build up archives from various perspectives inside and outside of the subject. Like a squirrel collecting nuts from all over the place. Sometimes the archives turn into patchwork, oftentimes not. The nipple archive stayed as nipples (kind of self-evident), but over time I’ve developed ways to materialize and share what I find interesting about archived material and stories I want to tell. That process led me to focus on patchworks as a general methodology. It makes sense for a Ding Dong like me to pull disparate pieces of information together in textile and illustration.

I’m still open to wherever the thousand-plus nipple photos want to go, if anywhere at all.

Andrea Brena [26.02.24 00:12 am]

Before talking about the role of archives in the public domain and their role in the creation of new collective identities and forms of knowledge, let's pause for a moment on that squirrel collecting nuts. Take us into your cove. How do you organize the information and ingredients from your work? What systems have you developed over the years to navigate the plethora of references that inform your work? What tools do you use, and what structures have you put in place? (To be more specific, how do you organize your feeds, bookmarks, folders, feel free to share screenshots, sketches, diagrams, anything you might have to illustrate a certain logic or architecture.)

Jason Page [27.02.24 09:30 am]

You've opened up a can of worms. This one takes a little longer to answer, but I’m working on it!

This might take a bit more leg (brain) work to explain. The starting point for my archiving is a deep-seated Pennsylvania Dutch urge not to throw anything away and an urge to collect overlooked materials for later use. I’ve got stuff archived (hoarded) at home, in the studio, on my computer, in my sketchbooks, on my phone, in drawers, boxes. There are systems; some overly organized and some organized chaos. My favorite game as a kid was the memory game. Archiving for me is about memorizing things by organizing them, knowing that I’ll forget 90% but also get to look at the material with new eyes when I see it later. I like to think of Jordan Firstman’s Instagram impression of someone who says they won’t forget an idea before going to bed and then forgets it. It’s less extreme than David Lynch’s idea that forgetting an idea will lead to death, but I am afraid that if I don’t archive an idea, an old chair on the street, thrift store textiles, photos of funny moments, they will just disappear. I feel kinship with how Aaron Draplin talks about the value of junking and “Always looking at dead things.”

When I’m not wasting my life away on Instagram, I try to use it as a digital archive of work and life around it. Lately, I’ve been doing that more in my Ding Dong newsletter, but I still get excited about some of the Instagram archives I’ve built with the story collection feature and hashtags. It feels weird to say I get excited about hashtags, but it’s true. I have an ongoing stories collection of observations from my window in Amsterdam (titled Van Wowstraat). Knowing that there’s a place to house the work somehow makes it easier to make the work.

In 2016-2017, I documented my yearlong residency process at Atelier van Lieshout, Rotterdam, with #AmericaninResidence. The residency was about 9 months of collecting and three months of making work with the material. The hashtag made it easy to play the memory game and let the material mull around in my head until it wanted to come out.

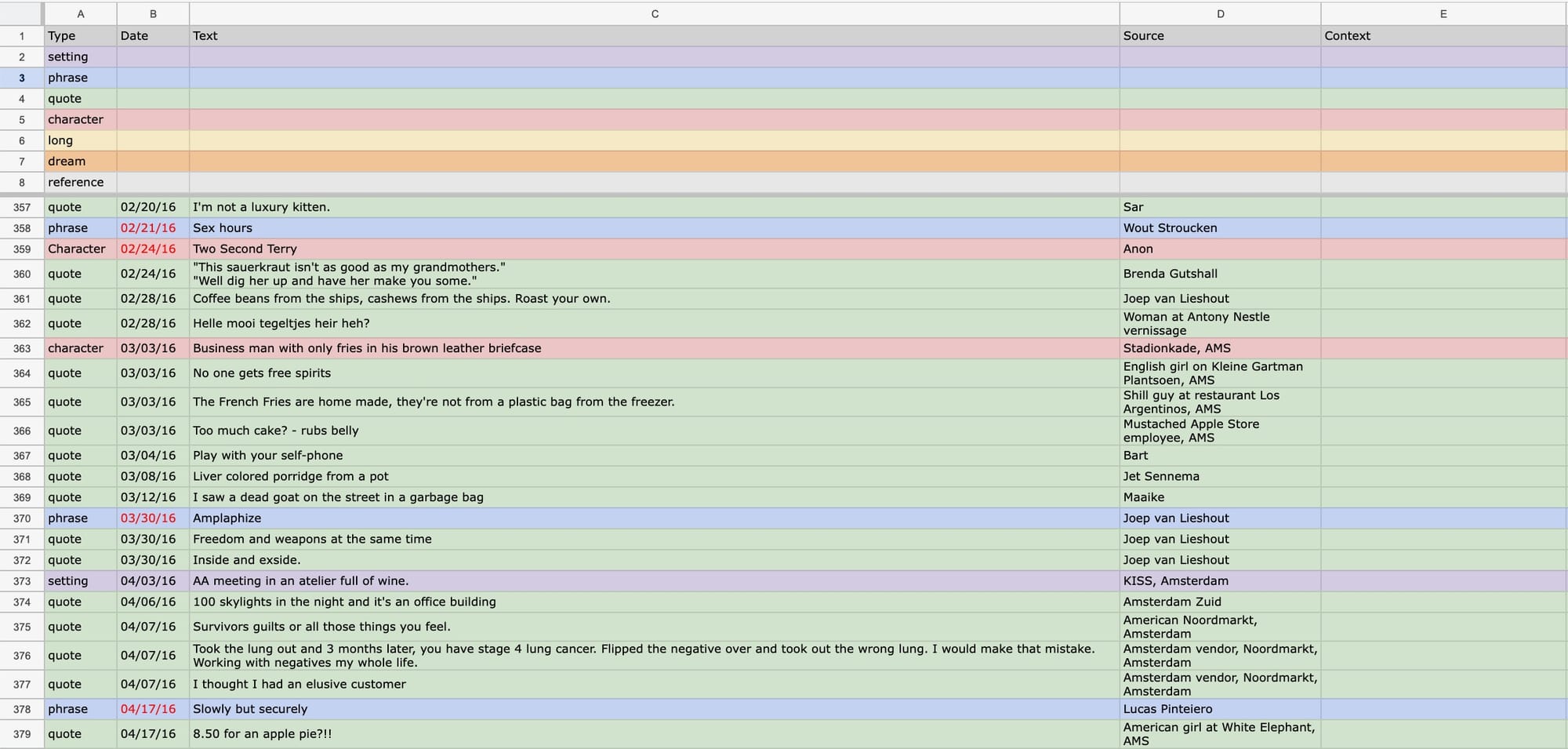

I really do enjoy organizing and archiving material on the computer, but once it’s nicely cataloged in the folder system, it’s damn easy to never look at it again. Still, I don’t know how I’d keep my head on if I didn’t use my research > design > process > print > press structure. One archive with no purpose other than the enjoyment of collecting and organizing is my ongoing Google Sheet of overheard & observed things (2011-present).

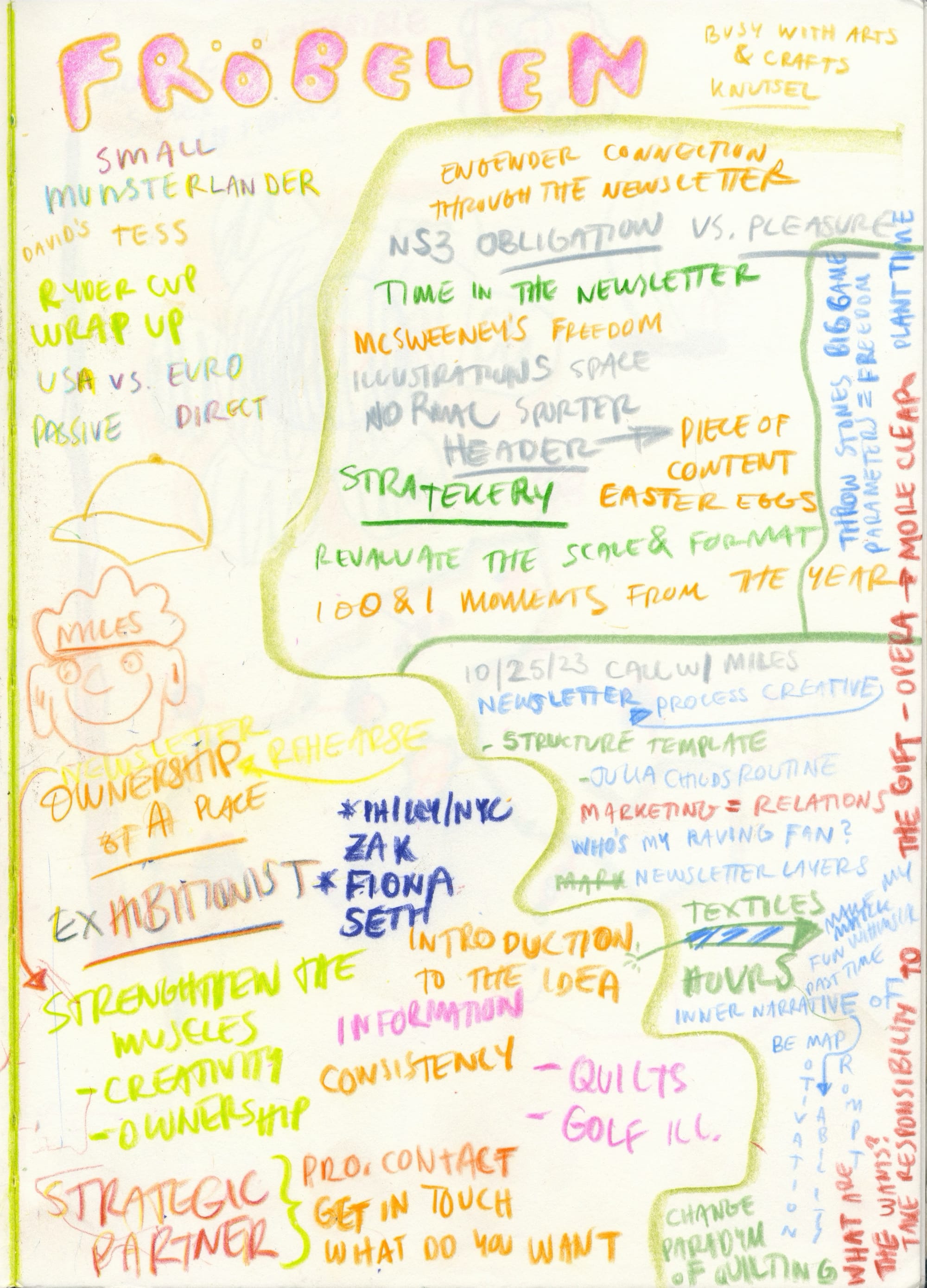

My sketchbooks work in a similar way, albeit much more chaotically. I use them to capture ideas, meetings, materials, and ah-ha moments together. There are a few ideas that keep popping up year after year in the sketchbooks. The cream rises to the top of the archive, or it doesn’t.

The studio is my main place of chaotic archiving/squirreling away physical material. Textiles, toys, books, garbage, art, samples, golf clubs, presents, clothes. In 2022, Johannes Schwartz visited the studio I share with my wife, Lotje van Lieshout (an artist with her own world of archived objects), to take photos for an exhibition. His images do a great job of capturing whatever “system” has grown over time. I’m a Ding Dong, and I like living with the material and seeing how things collide and sometimes seep into my patchwork.

Andrea Brena [03.03.24 08:34pm]

I hope I do not oversimplify if I say that you are a collector who builds both containers and structures, triggers to recall memories.

I love the concept of creating a place to house the work and to make the work because of that.

Could you expand and explain your process: research > design > process > print > press structure? Is this about materialization and tangibility?

Jason Page [04.03.24 11:34 pm]

That’s a pretty professional-looking description of my Ding Donging around. I’m going to borrow it someday! One tiny clarification would be that a lot of my projects try to capture moments now that would normally be recalled as memories later. Fueled by the fear of forgetting, of course.

In my work, I’m looking for the right packages/vehicles to carry an idea. Sometimes that’s an illustration or a quilt, artwork, publication, or, more recently, a newsletter. A quilted patchwork is the same as collaged artwork in my book. They just use different materializations for different contexts. The process is a funny thing to talk about because there’s logic in the computer folders, but in practice, the process goes wherever it wants to go.

The research folder starts by casting a very wide and weird net. I think, What Would Laurie Anderson Do? Digital junking. I dig into internet archives for hard-to-find books, screenshot old YouTube videos, stalk people’s Instagrams, go through my camera roll on the toilet, surf second-hand marketplaces, etcetera. I’m looking for any visual cues to build narratives with. The material doesn’t need to make sense to make it into the research folder. It just has to trigger some creative impulse.

Once the Research folder is fat and happy, I make a selection for the design (physical or digital). Usually, the first idea goes down a lame road, and I have to start a new design, sometimes I’m lucky, and the research gets me close in the first go. I try to get the first layer down as quickly as possible so there’s something to react to. Reacting is where the process (and fun) comes in. In the digital world, where vectors are free (Aaron Draplin), I’m copy-pasting, looking, adjusting, copy-pasting, adjusting, forever. In the physical world, the process means moving pieces around into different compositions, taking lots of photos, and letting the work stew on the table/wall. Live with the work. In both worlds, I need to see the work in its different options to decide where to go.

Printing is deciding what goes out into the world and usually happens in a mad dash. There’s nothing as inspiring as a deadline.

The Press folder starts after the rush of finishing a project dies down. A lot of my projects are made in collaboration with golf media companies that have their own photography departments (that are great). For my own Ding Dong press, I try to have as much (or more) fun with the presentation of the work as I did with the work itself. I like crow-barring the golf illustrations back into photos of the golf world. Press is fun if it’s not real press.

Looping back to your question. I guess the works are containers themselves, and the folders are containers to make a bit more sense of the material and process.

Andrea Brena [07.03.24 07:33 am]

Thank you, Jason. I can envision how materials and elements of your archive bubble up to the surface every now and again and show up differently depending on the context and the circumstances of the moment. As our time is up, I thank you very much for your time. This “epistolary” interview, while being run in the small pockets of time in between our daily errands, has kept my mind centered around your work and your words for the last two weeks and, in one way or another, has strengthened a connection weakened by the ticking of time. To close, is there anything I did not ask you about your practice that you would like to share with our readers? It’s been a pleasure, my friend!

Jason Page [07.03.24 08:34 pm]

It’s been a real pleasure to think through these questions with you. The last two weeks were a good example of how hectic a creative life can be (not complaining), so it was especially nice to come home from the studio tired and take a moment to reflect on methodologies and some forgotten tidbits from the archive. It’s easy to forget about things when life keeps zooming forward.

If you have enjoyed this interview and this Hotpot issue consider subscribing and forwarding this email or URL to a friend.

Don't forget to check out Jason's work and his Ding Dong newsletter

Thank you very much for your continued support and big ups to Jason for his trust and time throughout the last couple of weeks.

See you soon!